It took a lot of guts to quit my dream job.

I was finally on the career path I’d aspired to for so long: reporting for public radio. I’d been at Wyoming’s NPR station for almost three years and the job was wonderful in many ways. I had lots of autonomy, I liked my colleagues, I was good at what I did, and the work felt meaningful. But I didn’t love it — not enough anyway. As the months (and then years) ticked by, a quote from Henry David Thoreau kept floating through my thoughts. “The mass of men live lives of quiet desperation.” It didn’t help that my mother had passed away several years earlier, and I’d never taken time to fully grieve.

Then I read Cheryl Strayed’s “Wild”.

“YES,” I thought immediately. If Cheryl Strayed could get over her mother’s untimely death and a heroin problem by hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, maybe a long-distance hike would help me, too. I settled on the Colorado Trail, a 500-mile footpath through the Rocky Mountains, which leads from Denver to Durango. My goals for hiking the trail were simple: I wanted to come to terms with my grief, kick the depression that had settled in, and figure out my life calling. Simple.

The doubts and misgivings set in almost immediately.

On a practical level, I didn’t know anything about backpacking. The longest I’d ever been out was two nights, and I’d never gone solo. Then there were the career worries. Taking so much time off would leave a gap in my resume; what if I couldn’t find a job when I got back? Plus, wasn’t it misguided to leave a position I’d worked so hard to get? A few months before I set out, a family friend questioned my expectations for the hike. “What do think is going to happen out there?” she asked. “Do you really think the clouds are going to part and give you all the answers?”

When she put it that way, my plan did sound a little silly.

In the end, the desire to get away from everything was so acute, so visceral, that it eclipsed my misgivings. I saved up money, bought a new blue backpack and a tiny orange tent, lined up someone to take care of my high-maintenance cat for the summer, and told my boss I was leaving.

Taking this leap of faith was one of the scariest things I had ever done. But it also led to what I’m doing today — to a career that brings me more joy than I thought possible.

Turns out my mom’s friend was right. The clouds didn’t part and provide all the answers. I had pictured myself walking along the Colorado Trail, thinking deep thoughts all day. But the trail kept wrenching my mind back to reality. The rain, the blisters, the mosquitoes, the broken gear — it all kept me fixated squarely on the present. There wasn’t much time left for deep thoughts.

But after I finished the trail, things quickly clicked into place.

I had dabbled with the idea of starting an outdoor-related podcast for some time, but I didn’t have a clear vision for what the focus would be. Plus, with a full-time job, I didn’t have the bandwidth to launch a demanding side project.

Now, I had nothing but time. And lots of ideas. While the Colorado Trail hadn’t provided the clear, concrete answers I thought I needed, it HAD given me much-needed mental space. And it had yielded some surprising realizations about life and society.

I’d seen how rich a fleeting connection with another person could be, in the absence of cell phones and other “real-world” distractions.

I’d realized that the things I used to shy away from (like risk taking) often actually made my life better. And I’d learned that loneliness and being alone are not synonymous. If five weeks on the trail could give me so much clarity, I thought, maybe narratives about the outdoors could help others sort out their own lives. Maybe telling big-picture stories through the lens of nature could give people a way to see their world a little differently, and ease the anxieties of adulting.

And so, the podcast “Out There” was was born.

Unlike most outdoor journalism, we don’t just recount people’s adventures; instead, we delve deep into life’s big questions. A story about a trip up Mount Everest looks at how humans make moral decisions. A piece about air quality in India asks whether you have the right to complain, if others are worse off. And an episode about a solo backpacking trip explains why you can be strong and independent — and still need help.

Three and a half years in, our team is still tiny, and so is our profit margin. I cringe every time I have to call in favors because I can’t afford to pay someone. And I feel twinges of shame when I admit that the income from the show isn’t enough to support me yet.

But despite the financial challenges, I wake up almost every morning excited to get to work.

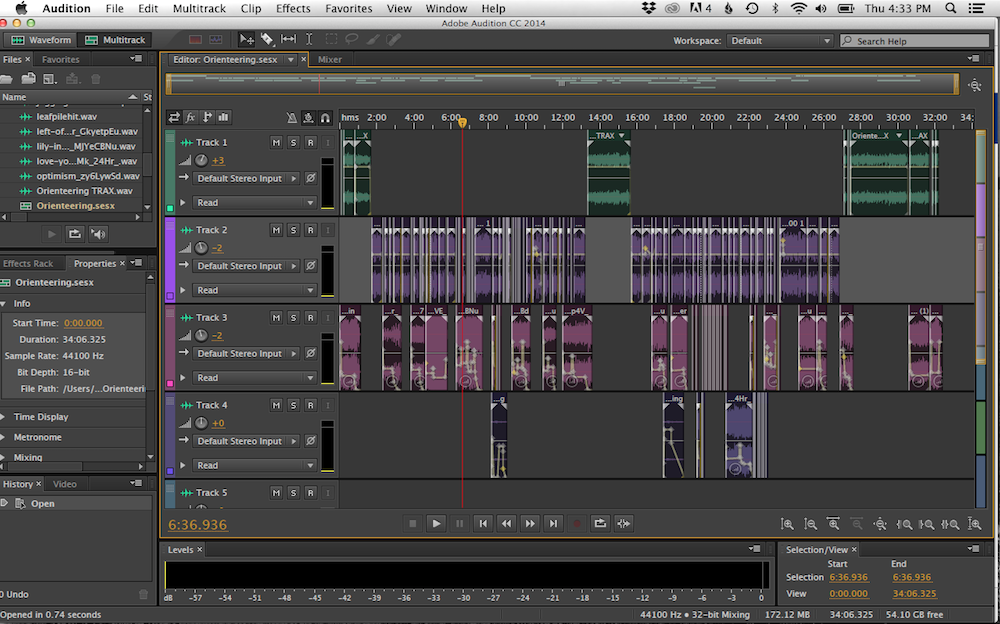

Sometimes, as I sit at my computer mixing a story, I find myself grinning — as if I’m getting away with something. Running an independent podcast is no walk in the park, but the joy it brings is intoxicating: pure, unadulterated pleasure. It’s the joy that comes from being able to do something you love — rather than just something you’re good at.